Bektashism

Flag of Bektashism, as seen at the World Headquarters of the Bektashi. | |

Emblem of Bektashism | |

| Abbreviation | Bektashism |

|---|---|

| Type | Dervish order |

| Headquarters | World Headquarters of the Bektashi, Tirana (previously Haji Bektash Veli Complex, Nevşehir) |

Region | Albania, Bulgaria, Greece, Kosovo, North Macedonia, Turkey, other Albanian diaspora (Italy, United States) and Turkish diaspora (Germany, France, Austria, Belgium) |

| Baba Mondi | |

Key people | |

| Part of a series on Bektashism |

|---|

|

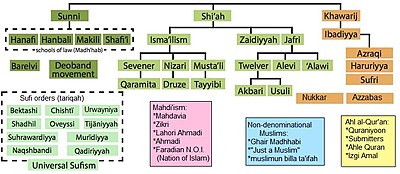

| Part of a series on Islam Sufism |

|---|

|

|

|

Bektashism (Albanian: Bektashi) is an mystic order of Sufi origin, that evolved in 13th-century Anatolia and became widespread in the Ottoman Empire. It is named after the saint Haji Bektash Veli. The Bektashian community is currently led by Baba Mondi, their eighth Bektashi Dedebaba, and is headquartered in Tirana, Albania.[6] Collectively, adherents of Bektashism are called Bektashians or simply Bektashis.[1][7]

The Bektashis were originally one of many Sufi orders within Sunni Islam. By the 16th century, the order had adopted some tenets of Twelver Shia Islam--including veneration of Ali (the son-in-law of Prophet Muhammad) and the Twelve Imams--as well as a variety of syncretic beliefs.

The Bektashis acquired political importance in the 15th century when the order dominated the Janissary Corps.[8] After the foundation of the Turkish Republic, the country's leader, Kemal Atatürk, banned religious institutions that were not part of the Directorate of Religious Affairs, and the community's headquarters relocated to Albania. Salih Nijazi was the last Dedebaba in Turkey and the first in Albania. The order became involved in Albanian politics, and some of its members, including Ismail Qemali, were major leaders of the Albanian National Awakening.

Bektashis believe in the ismah of the Islamic prophets and messengers, and the Fourteen Infallibles: the Prophet Muhammad, his daughter Fatima, and the Twelve Imams.[9] In contrast to many Twelver Shia, Bektashis respect all of the companions of Muhammad, including Abu Bakr, Umar, Uthman, Talha and Mu'awiya; but they consider Ali to be the greatest of all of the Prophet's companions.[10]

In addition to the spiritual teachings of Haji Bektash Veli, the Bektashi order was later significantly influenced during its formative period by the Hurufis (in the early 15th century), the Qalandariyya stream of Sufism, figures like Ahmad Yasawi, Yunus Emre, Shah Ismail, Shaykh Haydar, Nesimi, Pir Sultan Abdal, Gül Baba, Sarı Saltık and to varying degrees more broadly the Shia belief system circulating in Anatolia during the 14th to 16th centuries. The mystical practices and rituals of the Bektashi order were systematized and structured by Balım Sultan in the 16th century.

According to a 2005 estimate made by Reshat Bardhi, there are over seven million Bektashis worldwide, though more recent studies put the figure as high as 20 million.[11] In Albania, they make up 9% of the Muslim population and 5% of the country's population.[12] An additional 12.5 million Bektashis live in Turkey.[13] Bektashis are mainly found throughout Anatolia, the Balkans and among Ottoman-era Greek Muslim communities.[14] The term Alevi–Bektashi is currently a widely and frequently used expression in the religious discourse of Turkey as an umbrella term for the two religious groups of Alevism and Bektashism.[15]

History

[edit]Origins and establishment

[edit]

Bektashism originated in Anatolia as the followers of the 13th-century scholar Bektash,[16] who himself studied under Central Asian mystic Ahmad Yasawi.[17] The doctrines and rituals of the Bektashiyya were codified by the mystic Balim Sultan, who is considered the pīr-i thānī ('the Second Elder') by Bektashians.[16]

It was originally founded as a Sufi movement.[18][19] The branch became widespread in the Ottoman Empire, their lodges scattered throughout Anatolia as well as in the Balkans. It became the official order of the Janissary corps, the elite infantry corp of the Ottoman Army.[20] Therefore, they also became mainly associated with Anatolian and Balkan Muslims of Eastern Orthodox convert origin, mainly Albanians and northern Greeks (although most leading Bektashian babas were of southern Albanian origin).[21][failed verification] In 1826, the Bektashian order was banned throughout the Ottoman Empire by Sultan Mahmud II for having close ties with the Janissary corps.[20] Many Bektashian dervishes were exiled, and some were executed.[20] Their tekkes were destroyed and their revenues were confiscated.[20] This decision was supported by the Sunni religious elite as well as the leaders of other, more orthodox, Sufi orders. Bektashis slowly regained freedom with the coming of the Tanzimat era. After the foundation of the Turkish Republic, Kemal Atatürk shut down the lodges in 1925. Consequently, the Bektashian leadership moved to Albania and established their headquarters in the city of Tirana. Among the most famous followers of Bektashian in the 19th century Balkans were Ali Pasha[22][23][24][25][26][27] and Naim Frashëri.

Dedebabate

[edit]After lodges in Turkey were shut down, the order's headquarters moved to Albania.[28] On 20 March 1930, Salih Nijazi was elected as the Dedebaba of the Bektashian community in Albania. Prior to Nijazi, the Dedebaba was Haxhi Fejzullah in Turkey.[29] Njazi established the Bektashi World Headquarters in Tirana.[28] Its construction was finished in 1941 during the Italian occupation of Albania.[28] Nijazi promoted Bektashian Islam by introducing major ceremonies at popular tekkes.[28] After he was murdered, Ali Riza succeeded him as the Dedebaba.[28]

Despite the negative effect of the ban of lodges on Bektashian culture, most Bektashians in Turkey have been generally supportive of secularism to this day, since these reforms have relatively relaxed the religious intolerance that had historically been shown against them by the official Sunni establishment.

In the Balkans the Bektashian order had a considerable impact on the Islamization of many areas, primarily Albania and Bulgaria, as well as parts of Macedonia, particularly among Ottoman-era Greek Muslims from western Greek Macedonia such as the Vallahades. By the 18th century Bektashism began to gain a considerable hold over the population of southern Albania and northwestern Greece (Epirus and western Greek Macedonia). Following the ban on Sufi orders in the Republic of Turkey, the Bektashian community's headquarters was moved from Hacıbektaş in central Anatolia, to Tirana, Albania. In Albania, the Bektashian community declared its separation from the Sunni community and they were perceived ever after as a distinct Islamic sect rather than a branch of Sunni Islam. Bektashism continued to flourish until the Second World War. After the communists took power in 1945, several babas and dervishes were executed and a gradual constriction of Bektashian influence began. Ultimately, in 1967 all tekkes were shut down when Enver Hoxha banned all religious practice. When this ban was rescinded in 1990 the Bektashism reestablished itself, although there were few left with any real knowledge of the spiritual path. Nevertheless, many "tekkes" (lodges) operate today in Albania. The most recent head of the order in Albania was Hajji Reshat Bardhi Dedebaba (1935–2011) and the main tekke has been reopened in Tirana. In June 2011 Baba Edmond Brahimaj was chosen as the head of the Bektashian order by a council of Albanian babas. Today sympathy for the order is generally widespread in Albania where approximately 20% of Muslims identify themselves as having some connection to Bektashism.

There are also important Bektashian communities among the Albanian communities of North Macedonia and Kosovo, the most important being the Arabati Baba Teḱe in the city of Tetovo, which was until recently under the guidance of Baba Tahir Emini (1941–2006). Following the death of Baba Tahir Emini, the dedelik of Tirana appointed Baba Edmond Brahimaj (known as Baba Mondi), formerly head of the Turan Tekke of Korçë, to oversee the Harabati baba tekke. A splinter branch of the order has recently sprung up in the town of Kičevo which has ties to the Turkish Bektashian community under Haydar Ercan Dede rather than Tirana. A smaller Bektashian tekke, the Dikmen Baba Tekkesi, is in operation in the Turkish-speaking town of Kanatlarci, North Macedonia that also has stronger ties with Turkey's Bektashis. In Kosovo, the relatively small Bektashian community has a tekke in the town of Gjakovë and is under the leadership of Baba Mumin Lama and it recognizes the leadership of Tirana.

In Bulgaria, the türbes of Kıdlemi Baba, Ak Yazılı Baba, Demir Baba and Otman Baba function as heterodox Islamic pilgrimage sites and before 1842 were the centers of Bektashian tekkes.[30]

Bektashis continue to be active in Turkey and their semi-clandestine organizations can be found in Istanbul, Ankara and İzmir. There are currently two rival claimants to the dedebaba in Turkey: Mustafa Eke and Haydar Ercan.

A large functioning Bektashian tekke was also established in the United States in 1954 by Baba Rexheb. This tekke is found in the Detroit suburb of Taylor and the tomb (türbe) of Baba Rexheb continues to draw pilgrims of all faiths.

Arabati Baba Teḱe controversy

[edit]In 2002, a group of armed members of the Islamic Religious Community of Macedonia (ICM), a Sunni group that is the legally recognized organisation which claims to represent all Muslims in North Macedonia, invaded the Bektashian Order's Arabati Baba Teḱe in an attempt to reclaim this tekke as a mosque although the facility has never functioned as such. Subsequently, the Bektashian Order of North Macedonia sued the government for failing to restore the tekke to the Bektashians, pursuant to a law passed in the early 1990s returning properties previously nationalized under the Yugoslav government. The law, however, deals with restitution to private citizens, rather than religious communities.[31]

The ICM claim to the tekke is based upon their contention to represent all Muslims in North Macedonia; and indeed, they are one of two Muslim organizations recognized by the government, both Sunni. The Bektashian community filed for recognition as a separate religious community with the Macedonian government in 1993, but the Macedonian government has refused to recognize them.[31]

Proposed sovereign state

[edit]On 21 September 2024, it was reported that Prime Minister Edi Rama of Albania was planning to create the Sovereign State of the Bektashi Order, a sovereign microstate for the Order within Albania's capital of Tirana. Rama said the aim of the new state would be to promote religious tolerance and a moderate version of Islam.[32]

Beliefs

[edit]

Bektashis believe in God and follow all the prophets.[33] Bektashis claim the heritage of Haji Bektash Veli, who was a descendant of Ali, Husayn ibn Ali, Ali al-Sajjad and other Imams.[33][34] In contrast to many Twelver Shia, Bektashis respect all companions of Muhammad, including Abu Bakr, Umar, Uthman, Talha and Mu'awiya, though consider Ali to be the superior of all companions.[10]

Bektashians follow the teachings of Haji Bektash, who preached about the Twelve Imams. Bektashis differ from other Muslims by also following the Fourteen Innocents, who either died in infancy or were martyred with Husayn.[35] Abbas ibn Ali is also an important figure in Bektashism, and Bektashians visit Mount Tomorr to honor him during an annual pilgrimage to the Abbas Ali Türbe on August 20–25.[36]

In addition to the Muslim daily five prayers, Bektashians have two specific prayers, one at dawn and one at dusk for the welfare of all humanity.[33] Bektashism places much emphasis on the concept of Wahdat al-Wujud (Arabic: وحدة الوجود, romanized: Unity of Being) that was formulated by Ibn Arabi.

Malakat is an important text of Bektashian written by Haji Bektash.[37] Bektashis also follow the Quran and Hadith.

Bektashis follow the modern-day Bektashian Dedebabate, currently headed by Baba Mondi. Bektashis consider the dedebaba as their leader overseeing the entire branch.

Bektashism is also heavily permeated with Shiite concepts, such as the marked reverence of Ali, the Twelve Imams, and the ritual commemoration of Ashura marking the Battle of Karbala. The old Persian holiday of Nowruz is celebrated by Bektashis as Ali's birthday (see also Nevruz in Albania).

The Bektashian Order is a Sufi order and shares much in common with other Islamic mystical movements, such as the need for an experienced spiritual guide—called a baba in Bektashian parlance — as well as the doctrine of "the four gates that must be traversed": the "Sharia" (religious law), "Tariqah" (the spiritual path), "Marifa" (true knowledge), "Haqiqa" (truth).

There are many other practices and ceremonies that share similarities with other faiths, such as a ritual meal (muhabbet) and yearly confession of sins to a baba (magfirat-i zunub مغفرة الذنوب). Bektashis base their practices and rituals on their non-orthodox and mystical interpretation and understanding of the Quran and the prophetic practice (Sunnah). They have no written doctrine specific to them, thus rules and rituals may differ depending on under whose influence one has been taught. Bektashis generally revere Sufi mystics outside of their own order, such as ibn Arabi, al-Ghazali and Rumi, who are close in spirit to them despite many of being from more mainstream Islamic backgrounds.

As with other Muslims, Bektashis do not consume pork and consider it haram ("prohibited") and in addition, also do not consider rabbit.[38][39] Rakia, a fruit brandy, is used as a sacramental element by in Bektashism,[40] and Alevi Jem ceremonies, where it is not considered alcoholic and is referred to as "dem".[41]

Poetry and literature

[edit]| Part of a series on the Alevis Alevism |

|---|

|

|

Poetry plays an important role in the transmission of Bektashian spirituality. Several important Ottoman-era poets were Bektashis, and Yunus Emre, the most acclaimed poet of the Turkish language, is generally recognized as a subscriber to the Bektashian order.

Like many Sufis, the Bektashis were quite lax in observing daily Muslim laws, and women as well as men took part in ritual wine drinking and dancing during devotional ceremonies. The Bektashis in the Balkans adapted such Christian practices as the ritual sharing of bread and the confession of sins. Bektashi mystical writings made a rich contribution to Sufi poetry.[42]

A poem from Bektashi poet Balım Sultan (died c. 1517/1519):

- İstivayı özler gözüm, (My eye seeks out repose,)

- Seb'al-mesânîdir yüzüm, (my face is the 'oft repeated seven (i.e. the Sura Al-Fatiha),)

- Ene'l-Hakk'ı söyler sözüm, (My words proclaim "I am the Truth",)

- Miracımız dardır bizim, (Our ascension is (by means of) the scaffold,)

- Haber aldık muhkemattan, (We have become aware through the "firm letters",)

- Geçmeyiz zâttan sıfattan, (We will not abandon essence or attributes,)

- Balım nihan söyler Hakk'tan, (Balım speaks arcanely of God)

- İrşâdımız sırdır bizim. (Our teaching is a mystery.[43])

Community hierarchy

[edit]Like most other Sufi orders, Bektashism is initiatic, and members must traverse various levels or ranks as they progress along the spiritual path to the Reality. The Turkish names are given below, followed by their Arabic and Albanian equivalents.[44]

- First-level members are called aşıks عاشق (Albanian: ashik). They are those who, while not having taken initiation into the order, are nevertheless drawn to it.

- Following initiation (called nasip), one becomes a mühip محب (Albanian: muhib).

- After some time as a mühip, one can take further vows and become a dervish.

- The next level above dervish is that of baba. The baba (lit. father) (Albanian: atë) is considered to be the head of a tekke and qualified to give spiritual guidance (irshad إرشاد).

- Above the baba (Albanian: gjysh) is the rank of halife-baba (or dede, grandfather).

- The dedebaba (Albanian: kryegjysh) is traditionally considered to be the highest ranking authority in the Bektashian Order. Traditionally the residence of the dedebaba was the Pir Evi (The Saint's Home) which was located in the shrine of Hajji Bektash Wali in the central Anatolian town of Hacıbektaş (aka Solucakarahüyük), known as the Hajibektash complex.

Traditionally there were twelve of these hierarchical rankings, the most senior being the dedebaba (great-grandfather).

Administration

[edit]In Albania, the World Headquarters of the Bektashi (Albanian: Kryegjyshata) divides the country into 6 different administrative districts (similar to Christian parishes and patriarchates), each of which is called a gjyshata.[44]

- The Gjyshata of Gjirokastra (headquarters: tekke of Asim Bab): the regions of Gjirokastra, Saranda and Tepelena.

- The Gjyshata of Korça (headquarters: tekke of Turan): the regions of Korça, Devoll, Pogradec and Kolonja, including Leskovik.

- The Gjyshata of Kruja (headquarters: tekke of Fushë Kruj): the regions of Kruja, Kurbin, Bulqiza, Dibra, Mat, Shkodra and Durrës.

- The Gjyshata of Elbasan (headquarters: tekke of Baba Xhefai): the regions of Elbasan, Gramsh, Peqin, Lushnja, Kavaja, and Librazhd, including Përrenjas.

- The Gjyshata of Vlora (headquarters: tekke of Kusum Bab): the regions of Vlora, Mallakastra, Fier, including Patos and Roskovec.

- The Gjyshata of Berat (headquarters: tekke of Prisht): the regions of Berat, Skrapar and Përmet.

During the 1930s, the six gjyshata of Albania set up by Sali Njazi were:[44]

- Kruja, headquartered at the tekke of Fushë-Krujë

- Elbasan, headquartered at the tekke of Krastë, Dibër

- Korça, headquartered at the tekke of Melçan

- Gjirokastra, headquartered at the tekke of Asim Baba

- Prishta, representing Berat and part of Përmet

- Vlora, headquartered at the tekke of Frashër

National headquarters in other countries are located in:[45]

There is also a Bektashian office in Brussels, Belgium.[46]

World Bektashi Congress

[edit]The World Bektashi Congress, also called the National Congress of the Bektashi, a conference during which members of the Bektashi Community make important decisions, has been held in Albania several times. Since 1945, it has been held exclusively in Tirana. The longest gap between two congresses lasted from 1950 to 1993, when congresses could not be held during Communist rule in Albania. A list of congresses is given below.[44][47]

| No. | Congress | Date | Location | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | First National Congress of the Bektashi | 14–17 January 1921 | tekke of Prishta in the Skrapar region | The name Komuniteti Bektashian (Bektashi community) was adopted. |

| 2 | Second National Congress of the Bektashi | 8–9 July 1924 | Gjirokastra | |

| 3 | Third National Congress of the Bektashi | 23 September 1929 | tekke of Turan near Korça | The Bektashi declared themselves to be a religious community autonomous from other Islamic communities. |

| 4 | Fourth National Congress of the Bektashi | 5 May 1945 | Tirana | Xhafer Sadiku Dede was made kryegjysh (or dedebaba), and the influential Baba Faja Martaneshi, a communist collaborator, was made secretary general. |

| 5 | Fifth National Congress of the Bektashi | 16 April 1950 | Tirana | |

| 6 | Sixth National Congress of the Bektashi | 19–20 July 1993 | Tirana | |

| 7 | Seventh National Congress of the Bektashi | 23–24 September 2000 | Tirana | |

| 8 | Eighth National Congress of the Bektashi | 21 September 2005 | Tirana | |

| 9 | Ninth National Congress of the Bektashi | 6 July 2009 | Tirana |

List of Dedebabas

[edit]This section lists the Dedebabas (Supreme Leaders) of Bektashism.

In Turkey (before 1930)

[edit]List of Dedebabas (mostly based in Hacıbektaş, Anatolia), prior to the 1925 exodus of the Bektashian order from Turkey to Albania:[48]

- Haji Bektash Veli (1282-1341)

- Hidër Llalla (1341-1361)

- Resul Balli (1361-1441)

- Jusuf Balli (1400s)

- Myrsel Balli (1400s)

- Balım Sultan (1509-1516)

- Sersem Ali Dede Baba (1551–1569)

- Eihaxh Ahmed Dede Baba (1569–1569)

- Ak Abdulla Dede Baba (1569–1596)

- Kara Halil Dede Baba (1596–1628)

- Eihaxh Vahdeti Dede (1628–1649)

- Eihaxh Sejjid Mustafa Dede Baba (1649–1675)

- Ibrahim Agjah Dede Baba (1675–1689)

- Halil Ibrahim Dede Baba (1689–1714)

- Haxhi Hasan Dede Baba (1714–1736)

- Hanzade Mehmed Kylhan Dede (1736–1759)

- Sejjid Kara Ali Dede Baba (1759–1783)

- Sejjid Dede Baba (1783–1790)

- Haxhi Mehmed Nuri Dede Baba (1790–1799)

- Haxhi Halil Haki Dede Baba (1799–1813)

- Mehmed Nebi Dede Baba (1813–1834)

- Haxhi Ibrahim Dede Baba (1834–1835)

- Sejjid Haxhi Mahmud Dede Baba (1835–1846)

- Saatxhi Dede Baba (1846–1848)

- Sejjid Hasan Dede Baba (1848–1849)

- Elhaxh Ali Turabi Dede Baba (1849–1868)

- Haxhi Hasan Dede Baba (1868–1874)

- Perishan Hafizali Dede Baba (1874–1879)

- Mehmed Ali Hilmi Dede Baba (1879–1907)

- Haxhi Mehmed Ali Dede Baba (1907–1910)

- Haxhi Fejzullah Dede Baba (1910–1913)

- Sali Njazi Dede Baba (1913–1925)

In Albania (1930–present)

[edit]List of Bektashi Dedebabas following the 1925 exodus of the Bektashi Order from Turkey to Albania:

| No. | Portrait | Name | Term in office | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |

|

Salih Nijazi (1876–1941) |

20 March 1930[49] | 28 November 1941 |

| 11 years, 8 months and 8 days | ||||

| 2 |

|

Ali Riza (1882–1944) |

6 January 1942 | 22 February 1944 |

| 2 years, 1 month and 16 days | ||||

| 3 |

|

Kamber Ali (1869–1950) |

12 April 1944 | 1945 |

| 0 or 1 year | ||||

| 4 |

|

Xhafer Sadik (1874–1945) |

5 May 1945 | 2 August 1945 |

| 2 months and 28 days | ||||

| 5 |

|

Abaz Hilmi (1887–1947) |

6 September 1945 | 19 March 1947 |

| 1 year, 6 months and 13 days | ||||

| 6 |

|

Ahmet Myftar (1916–1980) |

8 June 1947 | 1958 |

| 9 or 10 years | ||||

| 7 |

|

Baba Reshat (1935–2011) |

20 July 1993 | 2 April 2011 |

| 17 years, 8 months and 13 days | ||||

| 8 |

|

Baba Mondi (1959) |

11 June 2011 | Incumbent |

| 13 years, 7 months and 14 days | ||||

Religious figures

[edit]- Abaz Hilmi, Dede Baba, of the Tekke of Frashër (1887–1947)

- Abbas ibn Ali

- Abdullah Baba of Melçan (1786–1857 (−1853?))

- Abedin Baba of Leskovik

- Adem Baba of Prizren (d. 1894)

- Adem Vexh-hi Baba of Gjakova (1841–1927)

- Ahmet Baba of Prishta (d. 1902)

- Ahmet Baba of Turan (1854–1928)

- Ahmet Karadja

- Ahmet Myftari, Dede Baba (1916–1980)

- Ahmet Sirri Baba of Mokattam (1895–1963)

- Ali Baba of Berat

- Ali Baba of Tomorr (1900–1948)

- Ali Baba Horasani of Fushë Kruja (d. 1562)

- Ali Haqi Baba of Gjirokastra (1827–1907)

- Ali Riza of Elbasan, Dede Baba (1876–1944)

- Alush Baba of Frashër (c. 1816–1896)

- Arshi Baba of Durballi Sultan (1906–2015)

- Arshi Baba of Gjirokastra (d. 1621)

- Asim Baba of Gjirokastra (d. 1796)

- Balim Sultan of Dimetoka (1457–1517)

- Dylgjer Hysejni of Elbasan (b. 1959)

- Edmond Brahimaj, Dede Baba (1910–1947)

- Faja Martaneshi Baba

- Fetah Baba of Backa

- Hajdar Hatemi Baba of Gjonëm (early 19th century)

- Hajdër Baba of Kardhiq (d. 1904)

- Haji Bektash Veli (1248–1337) (Albanian: Haxhi Bektashi Veli; Turkish: Hacı Bektaş Veli)

- Hasan Dede of Përmet

- Haxhi Baba Horasani of Përmet (d. 1620)

- Haxhi Baba of Fushë Kruja

- Hidër Baba of Makedonski Brod

- Hysen Baba of Melçan (d. 1914)

- Hysen Kukeli Baba of Fushë Kruja (1822–1893)

- Ibrahim Baba of Qesaraka (d. 1930)

- Ibrahim Xhefai Baba of Elbasan (d. 1829)

- Iljaz Vërzhezha, Dervish (d. 1923)

- Kamber Ali, Dede Baba (1869–1950)

- Kasem Baba of Kastoria (late 15th century)

- Kusum Baba of Vlora

- Lutfi Baba of Mokattam (1849–1942)

- Mehmet Baba of Fushë Kruja (1882–1934)

- Meleq Shëmbërdhenji Baba (1842–1918)

- Muharrem Baba of Frashër (early 19th century)

- Muharrem Mahzuni Baba of Durballi Sultan (d. 1867)

- Myrteza Baba of Fushë Kruja (1912–1947)

- Qazim Baba of Elbasan (1891–1962)

- Qazim Baba of Gjakova (1895–1981)

- Qamil Baba of Gllava (d. 1946)

- Reshat Bardhi, Dede Baba (1935–2011)

- Rexheb Baba of Gjirokastra (1901–1995)

- Salih Baba of Matohasanaj (19th to 20th centuries)

- Salih Nijazi, Dede Baba (1876–1941)

- Sari Saltik

- Seit Baba of Durballi Sultan (d. 1973)

- Selim Kaliçani Baba of Martanesh (1922–2001)

- Selim Ruhi Baba of Gjirokastra (1869–1944)

- Selman Xhemali Baba of Elbasan (d. 1949)

- Sersem Ali Baba of Tetova (d. 1569)

- Shemimi Baba of Fushë Kruja (1748–1803)

- Sulejman Baba of Gjirokastra (d. 1934)

- Tahir Nasibi Baba of Frashër (d. 1835)

- Tahir Baba of Prishta (19th century)

- Xhafer Sadiku, Dede Baba (1874–1945)

Gallery

[edit]-

Bektashi tekke of Gjakova, Kosovo, established in 1790

-

Kutuklu Baba Tekke in Greece

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ a b "Encyclopedia Iranica, "BEKTĀŠĪYA"". Archived from the original on 10 September 2015. Retrieved 24 June 2014.

- ^ "Encyclopedia Iranica, "ḤĀJĪ BEKTĀŠ"". Archived from the original on 17 May 2018. Retrieved 15 May 2018.

- ^ a b "ʿALĪ AL-AʿLĀ (d. 822/1419), also known as Amīr Sayyed ʿAlī, principal successor of Fażlallāh Astarābādī, founder of the Ḥorūfī sect". Archived from the original on 17 May 2018. Retrieved 15 May 2018.

- ^ "Encyclopedia Iranica, "ASTARĀBĀDĪ, FAŻLALLĀH" (d. 796/1394), founder of the Ḥorūfī religion, H. Algar". Archived from the original on 17 May 2019. Retrieved 15 May 2018.

- ^ "Encyclopedia Iranica, "HORUFISM" by H. Algar". Archived from the original on 17 May 2018. Retrieved 15 May 2018.

- ^ Gibb, H. A. R.; Kramers, J. H.; Lévi-Provençal, E.; Schacht, J.; Lewis, B. & Pellat, Ch., eds. (1960). "Bektāshiyya". The Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Volume I: A–B. Leiden: E. J. Brill. p. 1162. OCLC 495469456.

- ^ "The Bektashi Shi'as of Michigan: Pluralism and Orthodoxy within Twelver Shi'ism". shiablog.wcfia.harvard.edu. Archived from the original on 31 August 2021. Retrieved 31 August 2021.

- ^ "Bektashiyyah | Religion, Order, Beliefs, & Community | Britannica".

- ^ Moosa, Matti (1 February 1988). Extremist Shiites: The Ghulat Sects. Syracuse University Press. ISBN 978-0-8156-2411-0.

- ^ a b Baskel, Zekeriya (27 February 2013). Yunus Emre: The Sufi Poet in Love. Blue Dome Press. ISBN 978-1-935295-91-4.

- ^ Norman H. Gershman (2008). Besa: Muslims who Saved Jews in World War II (illustrated ed.). Syracuse University Press. p. 4. ISBN 9780815609346.

- ^ Census 2023

- ^ "Sabahat Akkiraz'dan Alevi raporu | soL haber". Retrieved 19 February 2024.

- ^ Ayhan Kaya (2016) The Alevi-Bektashi order in Turkey: syncreticism transcending national borders, Southeast European and Black Sea Studies, 16:2, 275–294, DOI: 10.1080/14683857.2015.1120465

- ^ "The Amalgamation of Two Religious Cultures: The Conceptual and Social History of Alevi-Bektashism". 12 May 2022.

- ^ a b Algar 1989.

- ^ Velet, Ayşe Değerli (June 2017). "Vesâik-i Bektaşiyân'da Yer Almayan Rumeli'deki Bektaşi Yapıları (1400-1826)". The Journal of Alevi Studies (13).

- ^ DOJA, ALBERT (2006). "A Political History of Bektashism from Ottoman Anatolia to Contemporary Turkey". Journal of Church and State. 48 (2): 423–450. doi:10.1093/jcs/48.2.423. ISSN 0021-969X. JSTOR 23922338.

- ^ J. K. Birge (1937), The Bektashi Order of Dervishes, London.

- ^ a b c d "The Effects of the abolition on the Bektashi – METU" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 July 2017.

- ^ Nicolle, David; pg 29

- ^ Miranda Vickers (1999), The Albanians: A Modern History, London: I.B. Tauris, p. 22, ISBN 9781441645005, archived from the original on 19 May 2016, retrieved 20 October 2015,

Around that time, Ali was converted to Bektashism by Baba Shemin of Kruja...

- ^ H.T.Norris (2006), Popular Sufism in Eastern Europe: Sufi Brotherhoods and the Dialogue with Christianity and 'Heterodoxy' (Routledge Sufi), Routledge Sufi series, Routledge, p. 79, ISBN 9780203961223, OCLC 85481562, archived from the original on 29 June 2016, retrieved 20 October 2015,

...and the tomb of Ali himself. Its headstone was capped by the crown (taj) of the Bektashi order.

- ^ Robert Elsie (2004), Historical Dictionary of Albania, European historical dictionaries, Scarecrow Press, p. 40, ISBN 9780810848726, OCLC 52347600, archived from the original on 28 April 2016, retrieved 20 October 2015,

Most of the Southern Albania and Epirus converted to Bektashism, initially under the influence of Ali Pasha Tepelena, "the Lion of Janina", who was himself a follower of the order.

- ^ Vassilis Nitsiakos (2010), On the Border: Transborder Mobility, Ethnic Groups and Boundaries along the Albanian-Greek Frontier (Balkan Border Crossings- Contributions to Balkan Ethnography), Berlin: Lit, p. 216, ISBN 9783643107930, OCLC 705271971, archived from the original on 5 May 2016, retrieved 20 October 2015,

Bektashism was widespread during the reign of Ali Pasha, a Bektashi himself,...

- ^ Gerlachlus Duijzings (2010), Religion and the Politics of Identity in Kosovo, New York: Columbia University Press, p. 82, ISBN 9780231120982, OCLC 43513230, archived from the original on 29 April 2016, retrieved 20 October 2015,

The most illustrious among them was Ali Pasha (1740–1822), who exploited the organisation and religious doctrine...

- ^ Stavro Skendi (1980), Balkan Cultural Studies, East European monographs, Boulder, p. 161, ISBN 9780914710660, OCLC 7058414, archived from the original on 2 May 2016, retrieved 12 November 2015,

The great expandion of Bektashism in southern Albania took place during the time of Ali Pasha Tepelena, who is believed to have been a Bektashi himself

- ^ a b c d e Elsie, Robert (2019). The Albanian Bektashi: history and culture of a Dervish order in the Balkans. London: I.B. Tauris. ISBN 978-1-78831-569-2. OCLC 1108619669.

- ^ "KRYEGJYSHËT BOTËROR". Kryegjyshata Boterore Bektashiane (in Albanian). Retrieved 12 October 2024.

- ^ Lewis, Stephen (2001). "The Ottoman Architectural Patrimony in Bulgaria". EJOS. 30 (IV). Utrecht. ISSN 0928-6802.

- ^ a b "Muslims of Macedonia" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 November 2015. Retrieved 14 March 2008.

- ^ Higgins, Andrew (21 September 2024). "Albania Plans to Create a Muslim State in Tirana as Symbol of Tolerance". The New York Times. Retrieved 21 September 2024.

- ^ a b c Chtatou, Dr Mohamed (23 April 2020). "Unveiling The Bektashi Sufi Order – Analysis". Eurasia Review. Retrieved 11 August 2021.

- ^ "The Bektashi Order of Dervishes". bektashiorder.com. Archived from the original on 18 August 2011.

- ^ Moosa, Matti (1 February 1988). Extremist Shiites: The Ghulat Sects. Syracuse University Press. ISBN 978-0-8156-2411-0.

- ^ Elsie 2001, "Tomor, Mount", pp. 252–254.

- ^ Borges, Jason (19 November 2019). "Haji Bektash Veli". Cappadocia History. Retrieved 9 September 2021.

- ^ Moosa, Matti (1 February 1988). Extremist Shiites: The Ghulat Sects. Syracuse University Press. ISBN 978-0-8156-2411-0.

- ^ Elsie, Robert (2010). Historical Dictionary of Albania. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0-8108-6188-6.

- ^ "The Bektashis have stopped hiding".

- ^ Soileau, Mark (August 2012). "Spreading the Sofra: Sharing and Partaking in the Bektashi Ritual Meal". History of Religions. 52 (1): 1–30. doi:10.1086/665961. JSTOR 10.1086/665961. Retrieved 5 June 2021.

- ^ "Bektashiyyah | Islamic sect". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 8 April 2021.

- ^ Algar, Hamid. The Hurufi Influence on Bektashism: Bektachiyya, Estudés sur l'ordre mystique des Bektachis et les groupes relevant de Hadji Bektach. Istanbul: Les Éditions Isis. pp. 39–53.

- ^ a b c d e Elsie, Robert (2019). The Albanian Bektashi: history and culture of a Dervish order in the Balkans. London: I.B. Tauris. ISBN 978-1-78831-569-2. OCLC 1108619669.

- ^ Bektashi Quarters (Gjyshatat). Kryegjyshata Botërore Bektashiane. Accessed 19 September 2021.

- ^ Office in Brussels. Kryegjyshata Botërore Bektashiane. Accessed 19 September 2021.

- ^ Kongreset Bektashiane. World Headquarters of the Bektashi. Accessed 19 September 2021. (in Albanian)

- ^ Kryegjyshët Botëror. Kryegjyshata Botërore Bektashiane. Accessed 19 September 2021.

- ^ Çuni, Nuri (28 January 2020). "Kryegjyshata Botrore Bektashiane/ Sot, 90-vjetori i ardhjes në Shqipëri të Kryegjyshit Botror të Bektashinjve, Sali Niazi Dedei. Kryegjyshi Botror, Haxhi Dede Edmond Brahimaj: Sot në Korçë zhvillohet aktiviteti për "Nderin e Kombit". Ja historia e plot e klerikut atdhetar". Gazeta Telegraf (in Albanian).

Bibliography

[edit]- Algar, Hamid (1989). "BEKTĀŠĪYA". Encyclopaedia Iranica. Vol. IV. pp. 118–122.

- Doja, Albert. 2006. "A political history of Bektashism from Ottoman Anatolia to Contemporary Turkey." Journal of Church and State 48 (2): 421–450. doi=10.1093/jcs/48.2.423.

- Doja, Albert. 2006. "A political history of Bektashism in Albania." Politics, Religion & Ideology 7 (1): 83–107. doi=10.1080/14690760500477919.

- Elsie, Robert (2001). A Dictionary of Albanian Religion, Mythology and Folk Culture. New York: New York University Press. ISBN 978-1-85065-570-1.

- Nicolle, David; UK (1995). The Janissaries (5th). Osprey Publishing. ISBN 1-85532-413-X.

- Muhammed Seyfeddin Ibn Zulfikari Derviş Ali; Bektaşi İkrar Ayini, Kalan Publishing, Translated from Ottoman Turkish by Mahir Ünsal Eriş, Ankara, 2007 Turkish

- Saggau, Emil BH. "Marginalised Islam: Christianity's role in the Sufi order of Bektashism." In Exploring the Multitude of Muslims in Europe, pp. 183–197. Brill, 2018.

Further reading

[edit]- Elsie, Robert (2019). The Albanian Bektashi: history and culture of a Dervish order in the Balkans. London: I.B. Tauris. ISBN 978-1-78831-569-2. OCLC 1108619669.

- Yürekli, Zeynep (2012). Architecture and hagiography in the Ottoman Empire : the politics of Bektashi shrines in the classical age. Farnham, Surrey Burlington, VT: Ashgate. ISBN 978-1-4094-1106-2. OCLC 776031990.

- Frashëri, Naim Bey. Fletore e Bektashinjet. Bucharest: Shtypëshkronjët të Shqipëtarëvet, 1896; Reprint: Salonica: Mbrothësia, 1909. 32 pp.

External links

[edit]- Official website of the Kryegjyshata Botërore Bektashiane (World Headquarters of the Bektashi)

- Videos and documentaries (in Albanian)

- History of the Bektashi Order of Dervishes

- Bektashi Order

- Alevism

- Dervish movements

- Islam in Albania

- Islam in Bulgaria

- Islamic mysticism

- Liberal and progressive movements within Islam

- Religion and alcohol

- Religious organizations established in the 13th century

- Shia Islam in Albania

- Shia Islam in Turkey

- Shia Sufi orders

- Turkish words and phrases

- Religious organizations based in Bulgaria

- 13th-century establishments in Asia