Yucca

| Yucca | |

|---|---|

| |

| Yucca elata in White Sands National Park, New Mexico | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Monocots |

| Order: | Asparagales |

| Family: | Asparagaceae |

| Subfamily: | Agavoideae |

| Genus: | Yucca L. |

| Species | |

|

See text | |

| |

| The country and state level distributions of Yucca in North America[1] | |

| Synonyms[1] | |

Yucca is a genus of plants which are also called yucca as a common name in English. The genus is made up of 50 species native to North America from Panama to a few areas of southern Canada. The genus is generally classified in the asparagus family in a subfamily with the Agave, though historically it was part of the lily family. It has at least 50 accepted species ranging from small shrubby plants to tree like giants like the Joshua Tree.

The tight relationship between the yucca plants and their polinators, the yucca moths from the Tegeticula and Parategeticula genuses, is well known as an example of evolutionary mutualism. The flowers of many species are eaten as food, particularly in Central America and Mexico.

Description

[edit]Yuccas are perennial plants that have one or more rosettes of long, pointed sword shaped leaves. Usually the leaves are stiff and fibrous, but a few species have fleshy leaves.[2] The leaves are numerous and arranged in spiral at the ends of stems or branches.[3] Plants can be a small shrub or be large with a form like a tree.[4] The surface of the leaves are hairless, but some have a very rough surface. About half of all species have fibers that peal off the edges of the leaves.[5] The leaves never have spines on their edges, but sometime are very finely toothed.[6]

Plants without stems or trunks grow from a thick underground caudex, a modified stem with growth at the end like in a palm tree.[7] Species that do not have trunks tend to be found in colder areas such as the Rocky Mountains, Great Plains, and eastern United States. While species with trunks are more common in the subtropics, deserts, and tropics to the south.[8] The largest of these tree yuccas is Yucca brevifolia, commonly known as the Joshua tree from the American southwest.[9] Every species grows in soil, except for Yucca lacandonica, which grows as an epiphyte.[10]

Some species have a scape, a long flowering stem without any leaves or bracts along its length, these are always less than 2.5 centimeters (1 in) in diameter. The inflorescence is usually upright, but in a few species bends over and hangs downward. The inflorcences can be a panicle, where the flowers are on branches off the main stem, or a raceme, where the flowers are attached directly by flower stalks to the main stem.[2] Though the plants live for many years and flower multiple times, each inflorsecence dies after setting seed.[10]

The flowers are large and showy, ranging from bell shaped to round like a globe.[4] The six tepals are white to cream or slightly green in color.[10] The tepals are thick and leathery in texture and in many species will have streaks on the three outermost in red, pink, maroon, purple, or brown.[11]

In about half of the species the fruit is a dry capsule and for the rest it is a fleshy fruit. Inside the fruit the seeds are tightly packed, flat, and black in color.[12] Dry capsules are held in an upright position while the soft ones hang downwards.[4]

Due to very similar characteristics of many species it is difficult to identify them without flowers or fruits. Many characteristics taken together are needed to make identifications, often including the size and color of the pistil, style, and flowers while alive.[13] Yuccas are distinct from Agave due to their usually less sucullent leaves, their thick flower petals, and lack of spines on leaf edges.[6]

Taxonomy

[edit]Yucca was first described and named by Carl Linnaeus in his book Species Plantarum, published in 1753.[1] The first work on the genus as a whole was published by George Engelmann in 1873.[14] A lectotype for the genus, a specimen of Yucca aloifolia, was designated by Nathaniel Lord Britton and John Adolph Shafer in 1908.[10]

In 1902 William Trelease published a paper separating out Clistoyucca and Samuela from Yucca,[2] along with his 1893 separation of Hesperoyucca from the genus.[15] Susan Delano McKelvey argued against this separation, though recognizing them as sections of Yucca. Though McKelvey did allow that Hesperoyucca might be recognized as a genus writing, "since a number of flower and fruit characters differ from those in all other sections." DNA investigations in the 1990s found support for Hesperoyucca.[2] As of 2025 Hesperoyucca is listed as accepted.[15]

Prior to the 1950s Yucca was placed in Liliaceae, the lily family, due to having a superior ovary. Since that time evidence of it being more closely related to the Agave genus has been accepted.[16] In particular the discovery that Yucca, like plants in Agave, has 5 large and 20 small chromosomes was a large factor in reconsidering their relationship.[17] In the APG III system, published in 2009, placed the genus into Asparagaceae in the Agavoideae subfamily.[18] This classification continued in APG IV.[19] However, some botanists prefer to classify this subfamily as a family named Agavaceae.[16]

Species

[edit]As of 2025[update] Plants of the World Online (POWO) and World Flora Online both list 50 valid species.[1][20] In addition, POWO lists three other species, Yucca jaegeriana (McKelvey) L.W.Lenz, Yucca muscipula Ayala-Hern., Ríos-Gómez, E.Solano & García-Mend., and Yucca pinicola Zamudio,[1] that WFO lists as unchecked or as a synonym of another species.[21][22][23] There is also one natural hybrid, Yucca × schottii, which was formerly listed as a species under various names.[24]

| Plant | Flowers | Species name | Year[25] | Range[25] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

Yucca aloifolia L. | 1753 | Southeastern US, Central and Southeastern Mexico |

|

|

Yucca angustissima Engelm. ex Trel. | 1902 | Arizona, Colorado, New Mexico, & Utah |

|

|

Yucca arkansana Trel. | 1902 | Arkansas, Kansas, Missouri, Oklahoma, & Texas |

|

|

Yucca baccata Torr. | 1859 | Southwestern US & Northern Mexico |

|

|

Yucca baileyi Wooton & Standl. | 1913 | Arizona, Colorado, New Mexico, & Utah |

|

|

Yucca brevifolia Engelm. | 1871 | Baja California Norte, western Arizona, southeastern California, southern Nevada, Sonora, & southwest Utah |

|

Yucca campestris McKelvey | 1947 | New Mexico & Texas | |

| Yucca capensis L.W.Lenz | 1998 | Baja California Sur | ||

|

Yucca carnerosana (Trel.) McKelvey | 1938 | Northeastern Mexico | |

|

|

Yucca cernua E.L.Keith | 2003 | Texas |

|

Yucca coahuilensis Matuda & I.Piña | 1980 | Coahuila | |

|

Yucca constricta Buckley | 1862[26] | Texas | |

|

|

Yucca decipiens Trel. | 1907 | Northeastern and southwestern Mexico |

|

Yucca declinata Laferr. | 1995 | Sonora | |

|

Yucca desmetiana Baker | 1870 | Chihuahua | |

|

|

Yucca elata (Engelm.) Engelm. | 1882 | Southwestern US & northern Mexico |

|

|

Yucca endlichiana Trel. | 1907 | Coahuila & Nuevo León |

|

Yucca faxoniana (Trel.) Sarg. | 1905 | Chihuahua, Coahuila, New Mexico, & Texas | |

| Yucca feeanoukiae Hochstätter | 2013 | Utah | ||

|

|

Yucca filamentosa L. | 1753 | Eastern United States |

|

|

Yucca filifera Chabaud | 1876[27] | Northeastern, central, & southwestern Mexico |

|

Yucca flaccida Haw. | 1819 | Eastern US & Ontario | |

|

|

Yucca gigantea Lem. | 1859 | Central America & southern Mexico[28] |

|

|

Yucca glauca Nutt. | 1813 | Central United States & Alberta |

|

Yucca gloriosa L. | 1753 | Southeastern United States | |

|

Yucca grandiflora Gentry | 1957 | Chihuahua, Sonora | |

|

|

Yucca harrimaniae Trel. | 1902 | Arizona, Colorado, New Mexico, Nevada, & Utah |

|

Yucca intermedia McKelvey | 1947 | Central New Mexico | |

|

Yucca jaliscensis (Trel.) Trel. | 1920 | Northeastern and southwestern Mexico | |

|

Yucca lacandonica Gómez Pompa & J.Valdés | 1962 | Campeche, Chiapas, Oaxaca, Tabasco, & Veracruz | |

|

Yucca linearifolia Clary | 1995 | Coahuila & Nuevo León | |

|

|

Yucca luminosa ined. | Northeastern Mexico[29] | |

|

Yucca madrensis Gentry | 1972 | Sonora & Chihuahua | |

|

Yucca mixtecana García-Mend. | 1998 | Oaxaca & Puebla | |

| Yucca necopina Shinners | 1958 | Texas | ||

|

Yucca neomexicana Wooton & Standl. | 1913 | Colorado, New Mexico, & Oklahoma | |

|

Yucca pallida McKelvey | 1947 | Texas | |

|

Yucca periculosa Baker | 1870 | Oaxaca, Puebla, Tlaxcala, & Veracruz | |

|

Yucca potosina Rzed. | 1955 | San Luis Potosi & Tamaulipas | |

|

Yucca queretaroensis Piña Luján | 1989 | Guanajuato, Hidalgo, Queretaro, & San Luis Potosi | |

|

Yucca reverchonii Trel. | 1911 | Coahuila & Texas | |

|

|

Yucca rostrata Engelm. ex Trel. | 1902 | Chihuahua, Coahuila, & Texas[30] |

|

Yucca rupicola Scheele | 1850 | Chihuahua, Coahuila, Nuevo León, Tamaulipas, & Texas | |

|

|

Yucca schidigera Roezl ex Ortgies | 1871 | Baja California Norte, Arizona, California, Nevada, Sonora, & Utah |

|

Yucca sterilis (Neese & S.L.Welsh) S.L.Welsh & L.C.Higgins | 2008 | Northeast Utah | |

| Yucca tenuistyla Trel. | 1902 | Texas | ||

|

|

Yucca thompsoniana Trel. | 1911 | Chihuahua, Coahuila, Durango, Nuevo León, & Texas |

|

|

Yucca treculiana Carrière | 1858 | Northeastern Mexico, New Mexico, & Texas[31] |

|

|

Yucca utahensis McKelvey | 1947 | Northwestern Arizona, southeastern Nevada, & southwestern Utah |

|

Yucca valida Brandegee | 1889 | Baja California Norte & Baja California Sur |

Names

[edit]In 1737 Linnaeus, in setting out his rules for the names of genera, wrote, "Generic names which have not a root derived from Greek or Latin are to be rejected."[32] However, in the case of Yucca and several other names he violated his own rule by adopting names derived from other languages.[33] The word was borrowed from the Carib language by Spanish as juca, starting with Amerigo Vespucci in 1497 referring to cassava.[34] It was first used to refer to the unrelated plants of the Yucca genus in a German travel account published in 1557.[10] This was used as the genus name by Linnaeus in his 1753 book Species Plantarum.[2][1]

The name yucca is used as an English common name for plant species in the genus. It is also known as Adam's needle or as Spanish-bayonet.[34][2] Other common names for some species include Spanish dagger, shin dagger, soapweed, or soaptree.[34][4] The name yucca can be confused with cassava, though the spelling yuca is often used to distinguish the food from plants in Yucca.[34]

The Aztecs living in Mexico call the local yucca species iczotl in Nahuatl, which gave the Spanish izote.[35]

Range and habitat

[edit]The natural range of the yuccas stretches across much of southern North America from Panama in the south as far north as Alberta in Canada.[1] The exact extent is disputed as though Yucca gigantea is listed by Plants of the World Online (POWO) and World Flora Online (WFO) as native to central America,[1][20] other sources like World Plants list it as introduced to all the nations of Central America.[25] Likewise, Yucca flaccida is listed as native to Onterio by POWO, WFO, and World Plants,[1][20][25] but is listed by VASCAN as introduced.[36]

Yuccas are generally accepted to be introduced to the islands Caribbean.[1][20]

The yuccas are xerophytic, plants with adapations to dry enviroments, with even those native to rainy habitats growing better when in drier areas.[37]

The smaller, freeze-tolerant species of yucca have two centers of diversity, one in Texas and other other on the Colorado Plateau. They are found generally to the north and east of the range in Chihuahuan Desert, the Trans-Pecos region, the Rocky Mountains, the Colorado Plateau, and the Great Plains. The tree like yuccas with fleshy fruits have a center of diversity in the Sonoran Desert. They are found mainly in Mexico while the tree like yuccas with spongy fruits are found only in the Mojave Desert.[38]

Ecology

[edit]

Yuccas have a very specialized mutualistic system of pollination.[39] Yuccca moths of in genus Tegeticula or Parategeticula pollinate the flowers and then lay their eggs in the seed capsules of yuccas.[40] Though, the some species of Tegeticula provide no benefit to the yuccas, laying eggs but not pollinating the flowers due to lacking the specialized parts for carrying pollen.[41] All species of yucca are polinated by at least one species of yucca moth.[42] The mutualism was first documented by Charles Valentine Riley in 1873.[43] This created much excitement in the scientific community. In a 1874 letter to his friend Joseph Dalton Hooker, Darwin called it, "the most wonderful case of fertilisation ever published".[44]

Instances of animal behaviors that are exclusively aimed at polination of plants, rather than just accompanying the animal gathering food, are quite rare. Female yucca moths have tentacle-like mouth parts that they use to gather pollen and then to deposit it on the reproductive parts.[40] In the 150 years following the discovery of this relationship it became one of the most famous of the documented plant and animal mutualisms along with the fig wasps and fig trees.[45]

About two-thirds of the moth species are limited to just one species of yucca. There is some evidence that the moths that visit a single species are guided to the flowers by distinct scents. All yucca moths species gather together inside of blooms to mate. The females of Tegeticula gather pollen and then peirce the yucca ovaries or styles to lay their eggs. After this they deposit their load of pollen to ensure the development of seeds. The female Parategeticula moths cut groves into flower stems, petals, or other parts to lay their eggs, but also use their mouthparts to deposit pollen on stigmas and into styles.[40] Though the reduction or local extinction of yucca moths can reduce the fertility of seeds or the numbers produced, there is not yet evidence that it reduces the populations of yuccas as they are relatively long lived.[46]

Yucca species are the host plants for the caterpillars of the widespread but uncommon yucca giant-skipper butterfly (Megathymus yuccae), which is found across the southern United States and northern Mexico.[47] The ursine giant skipper butterfly (Megathymus ursus), from southern Arizona, southern New Mexico, western Texas, and Nuevo León, also feeds on yuccas such as Schott's yucca (Yucca × schottii) and banana yucca (Yucca baccata). As does the more northerly Strecker's giant skipper (Megathymus streckeri), though on smaller species of yucca.[48]

Beetle herbivores include yucca weevils, in the Curculionidae.[49]

Uses

[edit]Yuccas are widely grown as ornamental plants in gardens.

Yucca plants have provided food and fibers to humans. Several yucca species have fleshy fruits that are edible, although the seed they contain are not. Additionally, the flowers are edible both cooked and raw and the young flowering stems of some species are edible when cooked, however others may be toxic. The leaves, roots, stems, and hearts of the plants are all toxic due to high levels of saponins.[50]

Yucca rhizomes have been extensively used to produce soaps, shampoos, detergents and are still used to a lesser extent for this today.[51] The leaves are still used to make trays and baskets in the southwestern US.[52] Research efforts have been made into making use of the fibers as a substitute for sisal or abacá. However, such efforts were abandoned after conclusion of the Second World War.[53]

Yucca extract, specifically from the rhizomes of Mojave yucca (Yucca schidigera), is also used as a foaming agent in some beverages such as root beer and soda.[54] Yucca powder is produced from yucca plants. Harvested logs are squeezed and the sap produced is then evaporated to produce the powder used in food, cosmetics, pharmaceuticals, and as animal feed additives.[55]

Cultivation

[edit]Very soon after the start of the Columbian exchange of plants across the Atlantic Ocean yuccas were planted in European gardens as ornamental plants with the first recorded bloom in England in 1604.[56] Though they were planted for productive uses in Mexico prior to the Spanish Conquest, it is not recorded if they used them for ornimental purposes.[57]

The spineless yucca (Yucca gigantea) is used as a common houseplant, though sometimes under the mistaken name of Yucca elephantipes.[58]

Yuccas are widely grown as architectural plants providing a dramatic accent to landscape design. They tolerate a range of conditions but are best grown in full sun in subtropical or mild temperate areas.[59] Some of the larger species of yucca are used as living barriers and fences.[51]

Several species of yucca can be grown outdoors in temperate climates, including:[59]

Gastronomy

[edit]The flower petals are commonly eaten in Central America and Mexico, but the plant's reproductive organs (the anthers and ovaries) are first removed because of their bitterness.[60][61]

In addition to being called flor de izote in Mexico yucca flowers are also called flores de palma (palm flowers) in Hidalgo and San Luis Potosí, guayas, cuaresmeñas, or chochos in Veracruz, and chochas in Tamaulipas. In central Mexico, in more rural places they are eaten as a food, as they were in pre-Hispanic times. Bunches are sold in public markets and eaten while very fresh and tender, before they become bitter. They are also cooked with scrambled eggs or in green chile salsa in this area.[62]

Another way that yucca flowers are served is in a sauce after roasting where they are called chochos in tomachile. It is served this way as a snack or with salads in the Los Tuxtlas region of Veracruz.[63] In the northern Mexican state of Coahuila yucca flowers are considered a traditional food for Lent.[64]

In Mexico the fleshy fruits of some yucca species are called datiles, the same word as for the fruit of the date palm, though they are unrelated. These fruits are used to produce alcoholic drinks.[62]

In Guatemala, they are boiled and eaten with lemon juice. In El Salvador, the tender tips of stems are eaten and known locally as cogollo de izote.[60]

These Central American and Mexican culinary traditions have been imported to the United States to areas such as Los Angeles where the flowers of the giant yucca are eaten in season in scrambled eggs, pupusas, and tacos. Before being used as an ingredient the petals are often blanched for five minutes, though they are also eaten raw in small amounts.[61]

Traditional uses

[edit]In rural Appalachian areas, species such as Yucca filamentosa are referred to as "meat hangers". With their sharp-spined tips, the tough, fibrous leaves were used to puncture meat and knotted to form a loop with which to hang meat for salt curing or in smokehouses.[citation needed]

The dried and split trunks of yuccas are soft and work well for a hearth in starting fires via friction.[65]

The young stalks of the soaptree yucca (Yucca elata) have been consumed by the Mescalero Apache. They are roasted over an open fire and then peeled to eat the soft interior. The flowers of the same species were frequently boiled to remove their bitter flavor or the flower pistol removed, as the most bitter part.[50]

Symbolism

[edit]The yucca flower is the state flower of New Mexico in the southwestern United States. No species name is given in the law;[66] however, the Secretary of State of New Mexico website notes that the soaptree yucca (Yucca elata) is one of the more widespread species in New Mexico.[67] It was offically designated as the state flower in 1927 by the state legislature after a survey of state students with the support of the New Mexico Federation of Women’s Clubs.[67]

The yucca, specifically Yucca gigantea, is also the national flower of El Salvador, where it is known as flor de izote.[61] It was officially designated the floral emblem in 1995.[68] Salvadorans often compare their ability to recover from periods of repression to the ability of the flor de izote to grow back after being cut.[69]

Gallery

[edit]-

Joshua trees (Yucca brevifolia), growing in the Mojave Desert

-

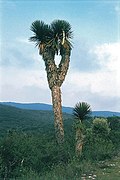

Unknown species near Orosí, Costa Rica

-

Yucca near Carlsbad Caverns National Park in New Mexico

-

Yucca harrimaniae also known as Harriman's yucca

-

Yucca faxoniana in Texas, with mature fruits

-

Yucca schidigera in Nevada, in full bloom

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j POWO 2025b.

- ^ a b c d e f Hess & Robbins 2020.

- ^ Welsh et al. 1987, p. 648.

- ^ a b c d Heil et al. 2013, p. 98.

- ^ Irish & Irish 2000, p. 32.

- ^ a b Ingram 2008, p. 163.

- ^ Churchill 1986, p. 1264.

- ^ Irish & Irish 2000, p. 33.

- ^ Linford 2007, p. 99.

- ^ a b c d e Thiede 2020, p. 363.

- ^ Irish & Irish 2000, p. 34.

- ^ Irish & Irish 2000, p. 36–37.

- ^ Heil et al. 2013, p. 99.

- ^ Irish & Irish 2000, p. 18.

- ^ a b POWO 2025a.

- ^ a b Thiede 2020, p. 364.

- ^ Oldfield 1997, p. 3.

- ^ Chase, Reveal & Fay 2009, pp. 133–134.

- ^ Angiosperm Phylogeny Group 2016, p. 15.

- ^ a b c d WFO 2025a.

- ^ WFO 2025b.

- ^ WFO 2025c.

- ^ WFO 2025d.

- ^ WFO 2025e.

- ^ a b c d Hassler 2025.

- ^ POWO 2025c.

- ^ POWO 2025d.

- ^ POWO 2025e.

- ^ POWO 2025f.

- ^ POWO 2025g.

- ^ POWO 2025h.

- ^ Stearn 1995, p. 275.

- ^ Stearn 1995, p. 289.

- ^ a b c d OED 2025.

- ^ RAE & ASALE 2024.

- ^ VASCAN 2025.

- ^ Guillot Ortiz & Van der Meer 2009, p. 7.

- ^ Clary & Simpson 1995, p. 79.

- ^ Irish & Irish 2000, p. 36.

- ^ a b c Smith & Leebens-Mack 2024, p. 376.

- ^ Althoff et al. 2006, p. 398.

- ^ Pellmyr 2003, p. 36.

- ^ Smith & Leebens-Mack 2024, pp. 377, 390.

- ^ Smith & Leebens-Mack 2024, pp. 376, 387.

- ^ Smith & Leebens-Mack 2024, pp. 375–376.

- ^ Oldfield 1997, p. 5.

- ^ Daniels 2009.

- ^ Opler & Tilden 1999, p. 476.

- ^ Chamorro & Anderson 2019, pp. 875, 883.

- ^ a b Tull 2013, p. 38.

- ^ a b Oldfield 1997, p. 6.

- ^ Buchanan 1987, p. 51.

- ^ Buchanan 1987, pp. 51–52.

- ^ Tanaka et al. 1996, p. 2.

- ^ Bononi et al. 2013, p. 239.

- ^ Irish & Irish 2000, pp. 49–50.

- ^ Irish & Irish 2000, p. 49.

- ^ Hodgson 2020.

- ^ a b Brickell 2003, p. 1093.

- ^ a b Pieroni 2005, p. 33.

- ^ a b c Spurrier 2013.

- ^ a b Muñoz Zurita 2000, p. 258.

- ^ Muñoz Zurita 2000, p. 182.

- ^ Muñoz Zurita 2000, p. 195.

- ^ Wescott 1999, p. 42.

- ^ New Mexico Legislature 2025.

- ^ a b NMOSOS 2025.

- ^ Castro 2023.

- ^ Murray & Barry 1995, p. 174.

Sources

[edit]Books

[edit]- Brickell, Christopher, ed. (2003). The Royal Horticultural Society A-Z Encyclopedia of Garden Plants. Vol. 2: K–Z (Revised ed.). London: Dorling Kindersley. ISBN 978-0-7513-3738-9. OCLC 54974082. Retrieved 18 April 2025.

- Buchanan, Rita (1987). A Weaver's Garden. Loveland, Colorado: Interweave Press. ISBN 978-0-934026-28-4. OCLC 15614076. Retrieved 18 April 2025.

- Churchill, Steven P. (1986). "106. Apiaceae". In McGregor, Ronald L.; Barkley, T. M.; Brooks, Ralph E.; Schofield, Eileen K. (eds.). Flora of the Great Plains. Lawrence, Kansas: University Press of Kansas. ISBN 978-0-7006-0295-7. OCLC 13093762. Retrieved 16 April 2025.

- Guillot Ortiz, Daniel; Van der Meer, Piet (2009) [In Print 2008]. El género Yucca L. en España [The genus Yucca L. in Spain] (PDF). Monografías de la Revista Bouteloua, 2 (in Spanish) (eBook ed.). Jaca, Spain: Jolube. ISBN 978-84-937291-8-9. OCLC 1123383406. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 May 2023. Retrieved 18 April 2025.

- Heil, Kenneth D.; O'Kane, Steve L. Jr.; Reeves, Linda Mary; Clifford, Arnold (2013). Flora of the Four Corners Region: Vascular Plants of the San Juan River Drainage, Arizona, Colorado, New Mexico, and Utah (First ed.). St. Louis, Missouri: Missouri Botanical Garden. ISBN 978-1-930723-84-9. ISSN 0161-1542. LCCN 2012949654. OCLC 859541992. Retrieved 15 April 2025.

- Ingram, Stephen (2008). Cacti, Agaves, and Yuccas of California and Nevada (First ed.). Los Olivos, California: Cachuma Press. ISBN 978-0-9789971-0-6. OCLC 190876422. Retrieved 25 April 2025.

- Irish, Mary; Irish, Mark (2000). Agaves, Yuccas, and Related Plants : A Gardener's Guide. Portland, Oregon: Timber Press. ISBN 978-0-88192-442-8. OCLC 41966994. Retrieved 17 April 2025.

- Linford, Jenny (2007). A Concise Guide to Trees (First ed.). Bath, England: Parragon. ISBN 978-1-4054-8801-3. OCLC 271753740. Retrieved 24 April 2025.

- Murray, Kevin; Barry, Tom (1995). Inside El Salvador (First ed.). Albuquerque, New Mexico: Interhemispheric Resource Center. ISBN 978-0-911213-53-9. OCLC 33403113. Retrieved 24 April 2025.

- Muñoz Zurita, Ricardo (2000). Diccionario Enciclopedico de Gastronomia Mexicana [Encyclopedic Dictionary of Mexican Gastronomy] (in Spanish) (First ed.). México: Editorial Clío. ISBN 978-970-663-094-0. OCLC 51687902. Retrieved 24 April 2025.

- Oldfield, Sara, ed. (1997). Cactus and Succulent Plants : Status Survey and Conservation Action Plan. Gland, Switzerland: IUCN. ISBN 978-2-8317-0390-9. OCLC 39162390. Retrieved 24 April 2025.

- Opler, Paul A.; Tilden, James W. (1999). A field Guide to Western Butterflies (Second ed.). Boston, Massachusetts: Houghton Mifflin Company. ISBN 978-0-395-79152-3. OCLC 1157041183. Retrieved 18 April 2025.

- Pieroni, Andrea (2005). "Gathering Food from the Wild". In Prance, Ghillean T.; Nesbitt, Mark (eds.). The cultural History of Plants. New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-92746-8. OCLC 57480711.

- Stearn, William T. (1995). Botanical Latin : History, Grammar, Syntax, Terminology, and Vocabulary (in English and Latin) (Fourth ed.). Portland, Oregon: Timber Press. ISBN 978-0-88192-321-6. OCLC 234102819. Retrieved 8 April 2025.

- Tanaka, Osamu; Tamura, Yukiyoshi; Masuda, Hitoshi; Mizutani, Kenji (1996). "Application of Saponins in Food and Cosmetics: Saponins of Mohave Yucca and Sapindus mukurossi". In Waller, George R.; Yamasaki, Kazuo (eds.). Saponins Used in Food and Agriculture. Advances in experimental medicine and biology, v. 405. New York: Plenum Press. ISBN 978-0-306-45394-6. OCLC 35229176. Retrieved 18 April 2025.

- Thiede, Joachim (2020). "Yucca AGAVACEAE". In Eggli, Urs; Nyffeler, Reto (eds.). Monocotyledons (Second ed.). Berlin, Germany: Springer. doi:10.1007/978-3-662-56486-8_109. ISBN 978-3-662-56486-8. OCLC 1145609055.

- Tull, Delena (2013). Edible and Useful Plants of the Southwest : Texas, New Mexico, and Arizona : including recipes, teas and spices, natural dyes, medicinal uses, poisonous plants, fibers, basketry, and industrial uses. Austin, Texas: University of Texas Press. ISBN 978-0-292-74827-9. OCLC 904364435.

- Welsh, Stanley L.; Atwood, N. Duane; Goodrich, Sherel; Higgins, Larry C. (1987). A Utah Flora. Great Basin Naturalist Memoirs, No. 9 (First ed.). Provo, Utah: Brigham Young University. JSTOR 23377658. OCLC 9986953694. Retrieved 16 April 2025.

- Wescott, David (1999). "The Hand-drill and Other Fires". In Wescott, David; Society of Primitive Technology (eds.). Primitive Technology : A Book of Earth Skills. Salt Lake City, Utah: Gibbs Smith Publisher. ISBN 978-0-87905-911-8. OCLC 40545399.

Journals

[edit]- Althoff, David M.; Segraves, Kari A.; Leebens-Mack, James; Pellmyr, Olle (1 June 2006). "Patterns of Speciation in the Yucca Moths: Parallel Species Radiations within the Tegeticula yuccasella Species Complex". Systematic Biology. 55 (3): 398–410. doi:10.1080/10635150600697325. ISSN 1063-5157. JSTOR 20142936. PMID 16684719. Retrieved 18 April 2025.

- Angiosperm Phylogeny Group; Chase, Mark W.; Christenhusz, Maarten J. M.; Fay, Michael F.; Byng, James W.; Judd, Walter S.; Soltis, Douglas E.; Mabberley, David J.; Sennikov, Alexander N.; Soltis, Pamela S.; Stevens, Peter F. (May 2016). "An update of the Angiosperm Phylogeny Group classification for the orders and families of flowering plants: APG IV". Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society. 181 (1): 1–20. doi:10.1111/boj.12385. ISSN 0024-4074.

- Bononi, M.; Guglielmi, G.; Rocchi, P.; Tateo, F. (2013). "First Data on the Antimicrobial Activity of Yucca filamentosa L. Bark Extracts" (PDF). Italian Journal of Food Science. 25 (2): 238–241. Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 August 2017. Retrieved 18 April 2025.

- Chamorro, M. L.; Anderson, Robert S. (19 December 2019). "Vauricia howdenae Chamorro and Anderson, a New Genus and Species of Rhinostomina from the Oriental Region, With a Key to World Genera of Orthognathini (Coleoptera: Curculionidae: Dryophthorinae)". The Coleopterists Bulletin. 73 (4): 875. doi:10.1649/0010-065X-73.4.875. ISSN 0010-065X. JSTOR 48571695. Retrieved 24 April 2025.

- Chase, Mark W.; Reveal, James L.; Fay, Michael F. (October 2009). "A subfamilial classification for the expanded asparagalean families Amaryllidaceae, Asparagaceae and Xanthorrhoeaceae". Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society. 161 (2): 132–136. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8339.2009.00999.x. ISSN 0024-4074.

- Clary, Karen H.; Simpson, Beryl B. (15 August 1995). "Systematics and character evolution of the genus Yucca L. (Agavaceae): Evidence from morphology and molecular analyses". Botanical Sciences (56 77–88). doi:10.17129/botsci.1466. ISSN 2007-4298.

- Pellmyr, Olle (2003). "Yuccas, Yucca Moths, and Coevolution: A Review". Annals of the Missouri Botanical Garden. 90 (1): 35–55. doi:10.2307/3298524. ISSN 0026-6493. JSTOR 3298524. Retrieved 24 April 2025.

- Smith, Christopher Irwin; Leebens-Mack, James H. (25 January 2024). "150 Years of Coevolution Research: Evolution and Ecology of Yucca Moths (Prodoxidae) and Their Hosts". Annual Review of Entomology. 69 (1): 375–391. doi:10.1146/annurev-ento-022723-104346. PMID 37758220. Archived from the original on 18 April 2025. Retrieved 18 April 2025.

News sources

[edit]- Spurrier, Jeff (30 April 2013). "The giant yucca's edible bounty: seeds, fruit, even flowers". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 22 December 2024. Retrieved 21 April 2025.

Web sources

[edit]- Acadia University; Université de Montréal Biodiversity Centre; University of Toronto Mississauga; University of British Columbia (2025). "Yucca flaccida - Database of Vascular Plants of Canada (VASCAN)". Canadensys. Retrieved 17 April 2025.

- Castro, Leyda (1 September 2023). "Nuestra Flor Nacional es la Pieza del Mes del MUHNES" [Our National Flower is the MUHNES Article of the Month]. El Museo de Historia Natural de El Salvador, Ministerio de Cultura, Gobierno de El Salvador [The Natural History Museum of El Salvador, Ministry of Culture, Government of El Salvador] (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 12 December 2024. Retrieved 21 April 2025.

- Daniels, Jaret C. (February 2009). "EENY 427/IN800: Yucca Giant-Skipper Butterfly, Megathymus yuccae (Boisduval & Leconte) (Insecta: Lepidoptera: Hesperiidae)". Ask IFAS - Powered by EDIS. Gainesville, Florida: University of Florida, IFAS Extension. Archived from the original on 28 March 2025. Retrieved 7 June 2010.

- Hassler, Michael (13 February 2025). "Synonymic Checklist and Distribution of the World Flora. Version 25.02". World Plants. Retrieved 15 April 2025.

- Hess, William J.; Robbins, R. Laurie (30 July 2020) [In print 2002]. "Yucca". Flora of North America. p. 423. ISBN 978-0-19-515208-1. OCLC 65199362. Archived from the original on 15 April 2025. Retrieved 15 April 2025.

- Hodgson, Larry (1 December 2020). "Yucca: the November 2020 Houseplant of the Month". Laidback Gardener. Archived from the original on 30 July 2023. Retrieved 18 April 2025.

- New Mexico Legislature (2025). Senate Bill 498. 57th Legislature - State of New Mexico. Archived from the original on 31 March 2025.

- NMOSOS (2025). "State Flower". New Mexico Office of the Secretary of State. Retrieved 24 April 2025.

- OED. "Yucca, N.". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/OED/5006883936. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- POWO (2025). "Hesperoyucca (Engelm.) Trel". Plants of the World Online. Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Retrieved 16 April 2025.

- POWO (2025). "Yucca L." Plants of the World Online. Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Retrieved 9 April 2025.

- POWO (2025). "Yucca constricta Buckley". Plants of the World Online. Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Retrieved 15 April 2025.

- POWO (2025). "Yucca filifera Chabaud". Plants of the World Online. Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Retrieved 15 April 2025.

- POWO (2025). "Yucca gigantea Lem". Plants of the World Online. Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Retrieved 15 April 2025.

- POWO (2025). "Yucca luminosa ined". Plants of the World Online. Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Retrieved 15 April 2025.

- POWO (2025). "Yucca rostrata Engelm. ex Trel". Plants of the World Online. Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Retrieved 15 April 2025.

- POWO (2025). "Yucca treculiana Carrière". Plants of the World Online. Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Retrieved 15 April 2025.

- RAE; ASALE (2024). "izote". Diccionario de la lengua española (in Spanish). Real Academia Española, Asociación de Academias de la Lengua Española. Archived from the original on 28 December 2024. Retrieved 23 November 2021.

- WFO (2025). "Yucca L." World Flora Online. Retrieved 9 April 2025.

- WFO (2025). "Yucca jaegeriana (McKelvey) L.W.Lenz". World Flora Online. Retrieved 15 April 2025.

- WFO (2025). "Yucca muscipula Ayala-Hern., Ríos-Gómez, E.Solano & García-Mend". World Flora Online. Retrieved 15 April 2025.

- WFO (2025). "Yucca pinicola Zamudio". World Flora Online. Retrieved 15 April 2025.

- WFO (2025). "Yucca × schottii Engelm. Zamudio". World Flora Online. Retrieved 24 April 2025.

External links

[edit] The dictionary definition of Yucca at Wiktionary

The dictionary definition of Yucca at Wiktionary- . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.